Basis trade and treasury deleveraging

Apr 12, 2025

Hedge funds are presented with an arbitrage opportunity in the first place, experts say, because of a fundamental imbalance in credit markets. Many asset managers of mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies have long-term liabilities—like payouts to retirees decades down the road—and want to buy assets with similar exposure to interest rates, or duration, over that span. The classic way of doing that often involves buying large amounts of Treasury futures contracts, but someone needs to take the other side of the trade. That’s where hedge funds and other broker-dealers step in, selling those derivatives while hedging that “short” position by buying cash Treasuries. In return, hedge funds profit off the spread between the value of the bond and the slightly overpriced futures contract: As the latter approaches expiry, its price falls and the short bet pays off. The profit comes from the price difference—the “basis”—between the futures contract and the underlying Treasury.

But, “this arrangement is inherently fragile,” according to a recent Brookings Institution paper by Harvard economist and former Fed governor Jeremy Stein along with the University of Chicago’s Anil Kashyap, Harvard’s Jonathan Wallen, and Columbia’s Joshua Younger. To make the trade worthwhile, hedge funds need to borrow heavily, sometimes using as much as 50- to 100-times leverage. When markets start going haywire, however, they can be vulnerable to margin calls or otherwise be pressured to liquidate their position when they sustain losses on other trades (especially as stock prices plummet) and investors pull their money.

A significant sell-off in U.S. Treasury markets triggered an abrupt shift in trade policy this week. An old foe of the Treasury market, the basis trade, has returned to the forefront of discussions. During the 2008 financial crisis, the basis trade was a major contributor to the dysfunction in the Treasury market. Again during COVID-induced volatility, hedge funds faced margin calls and unwound their basis trades. Broker-dealers absorbed these positions but were constrained by regulatory and balance-sheet limitations. This led to sharp dislocations in the Treasury market, including spikes in bid-ask spreads, repo intermediation spreads, and the cash-futures basis, similar to what we saw this week.Kashyap et al. (2025)

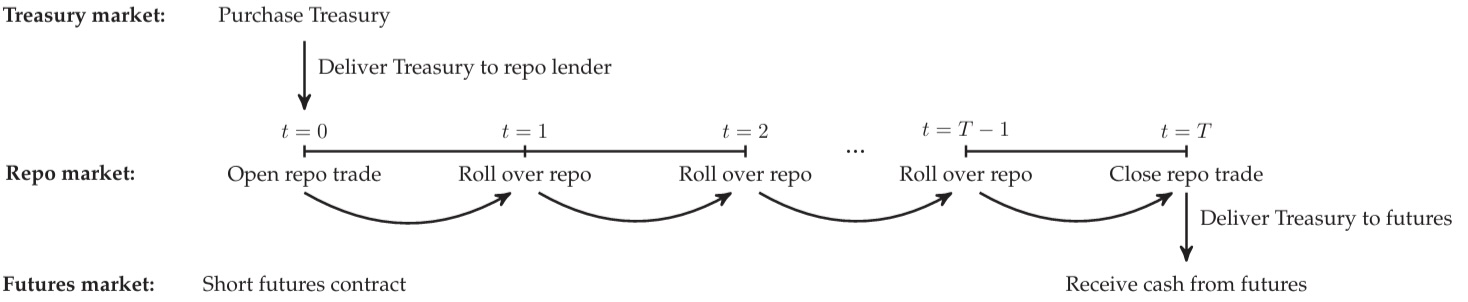

Asset managers (e.g., pension funds, insurers) seek long-duration exposure but often use Treasury derivatives like futures instead of cash Treasuries to conserve balance-sheet space for higher-yielding assets. Hedge funds and broker-dealers facilitate this by taking short positions in derivatives and offsetting them with long positions in cash Treasuries, profiting from the price differential (“basis”). Hedge funds finance these trades through repo borrowing, often with leverage ratios of 50-100x. This arrangement is fragile; shocks (e.g., margin calls or liquidity pressures) can force hedge funds to unwind positions rapidly.

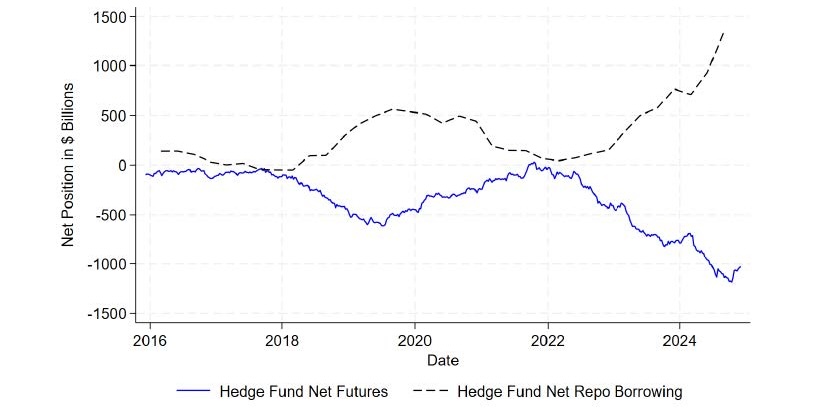

Concerns of the resurgence of the basis trade have been raised by the Fed, the treasury, and the Office of Financial Research (OFR). The OFR Barth and Kahn (2021); Barth et al. (2023)has been monitoring hedge fund activity in the Treasury market since 2021. They have observed a significant increase in hedge fund positions in Treasury futures and repo markets, which has raised concerns about potential financial stability risks. The OFR’s analysis indicates that hedge funds have been accumulating large positions in Treasury futures and repo markets, which could lead to increased volatility and liquidity risks in the Treasury market. This trend has been observed for several months now, and it is important to note that these developments were occurring well before the recent turmoil in the Treasury market.

Homebrew basis trade

Basis trade generally refers to a trading strategy that involves taking advantage of the price difference between a cash security and its corresponding futures contract. The basis is the difference between the cash price of a security and the futures price of that same security. Futures generally trade at a premium to cash prices, and the basis is typically positive. However, in some cases, the basis can be negative. This can occur when there is a lack of liquidity in the cash market or when there are significant differences in supply and demand between the two markets. Futures price converges to cash price as the contract approaches expiration. The basis trade is a strategy that seeks to profit from this convergence by taking long and short positions in the cash and futures markets, respectively.

A basis trade in US Treasuries typically involves exploiting the price difference (or “basis”) between a Treasury futures contract and the corresponding underlying cash bond (i.e., the deliverable Treasury security). A Treasury basis trade might be profitable because of inefficiencies between the futures market and the cash bond market. Futures prices imply a theoretical “implied repo rate”—the rate you’d earn if you bought the bond and sold the future. If this implied repo rate is higher than what you can actually finance the bond at in the repo market, you can:

- Buy the bond (cheap repo),

- Sell the future (rich implied financing),

- Capture the spread.

Here is how it works—don’t try it at home.

10-Year US Treasury Note Futures Contract (TYM5)

**Contract Details:**

- Symbol: ZN (TYM5)

- Description: US 10YR NOTE (CBT) Jun25

- Exchange: Chicago Board of Trade (CBT)

- Underlying: US 10yr 6%

- Contract Size: $100,000 USD

- Price: 109-23+ points

- Contract Value: $109,734.38

- Last Updated: 04/11/25

**Trading Specifications:**

- Tick Size: 1/64th (0-00+)

- Tick Value: $15.625

- Value of 1.0 point: $1,000

- Electronic Trading Hours: 18:00 - 17:00

**Key Dates:**

- First Trade: Fri 09/20/2024

- Last Trade: Wed 06/18/2025

- First Notice: Fri 05/30/2025

- First Delivery: Mon 06/02/2025

- Last Delivery: Mon 06/30/2025

**Performance:**

- Price Change (1D): -0.859/-0.777%

- Lifetime High: 115-21+

- Lifetime Low: 107-04+

**Margin Requirements:**

- Initial (Speculator): 2,062

- Initial (Hedger): 1,875

- Secondary (Both): 1,875

Carrying a Treasury security to delivery to the futures market through the repurchase agreement (repo) market. Barth and Kahn (2021).

Carrying a Treasury security to delivery to the futures market through the repurchase agreement (repo) market. Barth and Kahn (2021). Following Barth and Kahn’s (2021) convention, cash and futures prices are related through arbitrage:

\[P_{T} =\sum_{t} B_{t}c_t +B_{S}F_{S \to T}.\]You can get pre-calculated implied repo rates directly from the CME.

┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ US 10YR NOTE (CBT)Jun25 Bas.32nds Cash Contract │

│ T 4⅜ 01/31/32 (CTD) -0.106 100-08 109-23+ │

│ │

│ Conversion Factor: 0.9136 │

│ Settle: 04/14/2025 Delivery: 06/30/2025 │

│ 77 Days ACT/360 Act Repo%: 4.291 │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

| Cash Security | Price | Source | Conven Yield | Conver Factor | Gro/Bas (32nds) | Implied Repo% | Actual Repo% | Net/Bas (32nds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T 4 ⅜ 01/31/32 | 100-08 | BGN | 4.331 | 0.9136 | -0.106 | 4.317 | 4.291 | -0.182 |

| T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 100-31 3/4 | BGN | 4.327 | 0.9202 | 0.468 | 4.308 | 4.291 | -0.12 |

| T 4 ⅛ 02/29/32 | 98-24 1/4 | BGN | 4.335 | 0.9003 | -1.153 | 4.235 | 4.291 | 0.381 |

| T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 85-15+ | BGN | 4.351 | 0.7807 | -5.928 | 3.183 | 4.291 | 6.505 |

| T 4 ⅛ 03/31/32 | 98-24 1/4 | BGN | 4.333 | 0.8971 | 10.083 | 2.612 | 4.291 | 11.365 |

| T 2 ⅞ 05/15/32 | 91-01+ | BGN | 4.357 | 0.8286 | 3.871 | 2.476 | 4.291 | 11.332 |

| T 2 ¾ 08/15/32 | 89-29+ | BGN | 4.369 | 0.8164 | 10.711 | 1.295 | 4.291 | 18.533 |

| T 4 ⅛ 11/15/32 | 98-15+ | BGN | 4.361 | 0.891 | 22.753 | 0.745 | 4.291 | 24.015 |

| T 3 ½ 02/15/33 | 94-02 3/4 | BGN | 4.399 | 0.8508 | 23.166 | 0.101 | 4.291 | 27.141 |

| T 3 ⅜ 05/15/33 | 92-31 | BGN | 4.418 | 0.8391 | 28.5 | -0.901 | 4.291 | 33.172 |

| T 4 ⅜ 01/31/32 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | US TREASURY N/B | ID Number | 91282CMK4 |

| Industry | Treasury (BCLASS) | CUSIP | 91282CMK4 |

| Security Information | ISIN | US91282CMK44 | |

| Issue Date | 01/31/2025 | SEDOL 1 | BSPRXT1 |

| Interest Accrues | 01/31/2025 | FIGI | BBG01RYZYPJ1 |

| 1st Coupon Date | 07/31/2025 | Issuance & Trading | |

| Maturity Date | 01/31/2032 | Issue Price | 99.511534 |

| Floater Formula | N.A. | Risk Factor | 5.844 |

| Workout Date | 01/31/2032 | Amount Issued | 46,443 (MM) |

| Coupon | 4.375% | Security Type | USN |

| Cpn Frequency | S/A | Type | FIXED |

| Mty/Refund Type | NORMAL | Minimum Piece | 100 |

| Calc Type | STREET CONVENTION | Minimum Increment | 100 |

| Day Count | ACT/ACT | SOMA Holdings % | 5.26 |

| Market Sector | US GOVT | SOMA Holdings Amt | 2,443 (MM) |

| Country/Region | US | Currency | USD |

| Cash | Contract | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109-21+ | 109-22 | 109-22+ | 109-23 | 109-23+ | 109-24 | 109-24+ | 109-25 | 109-25+ | |

| 100-04+ | 4.564 | 4.630 | 4.696 | 4.762 | 4.828 | 4.894 | 4.960 | 5.027 | 5.093 |

| 100-05 | 4.491 | 4.557 | 4.623 | 4.689 | 4.755 | 4.821 | 4.887 | 4.953 | 5.020 |

| 100-05+ | 4.418 | 4.484 | 4.550 | 4.616 | 4.682 | 4.748 | 4.814 | 4.880 | 4.946 |

| 100-06 | 4.345 | 4.411 | 4.477 | 4.543 | 4.609 | 4.675 | 4.741 | 4.807 | 4.873 |

| 100-06+ | 4.272 | 4.338 | 4.404 | 4.470 | 4.536 | 4.602 | 4.668 | 4.734 | 4.800 |

| 100-07 | 4.199 | 4.265 | 4.331 | 4.397 | 4.463 | 4.529 | 4.595 | 4.661 | 4.727 |

| 100-07+ | 4.126 | 4.192 | 4.258 | 4.324 | 4.390 | 4.456 | 4.522 | 4.588 | 4.654 |

| 100-08 | 4.054 | 4.120 | 4.186 | 4.251 | 4.317 | 4.383 | 4.449 | 4.515 | 4.581 |

| 100-08+ | 3.981 | 4.047 | 4.113 | 4.179 | 4.245 | 4.311 | 4.377 | 4.443 | 4.509 |

| 100-09 | 3.908 | 3.974 | 4.040 | 4.106 | 4.172 | 4.238 | 4.304 | 4.370 | 4.436 |

| 100-09+ | 3.835 | 3.901 | 3.967 | 4.033 | 4.099 | 4.165 | 4.231 | 4.297 | 4.363 |

| 100-10 | 3.762 | 3.828 | 3.894 | 3.960 | 4.026 | 4.092 | 4.158 | 4.224 | 4.290 |

| 100-10+ | 3.689 | 3.755 | 3.821 | 3.887 | 3.953 | 4.019 | 4.085 | 4.151 | 4.217 |

| 100-11 | 3.617 | 3.683 | 3.749 | 3.815 | 3.880 | 3.946 | 4.012 | 4.078 | 4.144 |

| 100-11+ | 3.544 | 3.610 | 3.676 | 3.742 | 3.808 | 3.874 | 3.940 | 4.005 | 4.071 |

CTD is usually stable

| Trade Date | Futures Price | CTD Fwd Yield | Fut Fwd Risk | Conv Factor | Cheapest Issue | CTD Fwd Price | CTD Risk | G. Basis (32nds) | Implied Repo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 04/11/25 | 109.734375 | 4.33 | 6.224 | 0.9136 | T 4 ⅜ 01/31/32 | 100.253 | 0.394 | 4.245 | |

| 04/04/25 | 110.953125 | 4.127 | 6.216 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 102.095 | 5.935 | 0.215 | 4.325 |

| 03/28/25 | 111.2031 | 4.088 | 6.232 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 102.329 | 5.926 | -0.032 | 4.33 |

| 03/21/25 | 110.875 | 4.141 | 6.21 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 102.027 | 5.932 | 0.13 | 4.339 |

| 03/14/25 | 110.6406 | 4.179 | 6.195 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 101.811 | 5.918 | 0.532 | 4.299 |

| 03/07/25 | 110.578125 | 4.189 | 6.191 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 101.754 | 5.934 | 0.372 | 4.324 |

| 02/28/25 | 111.09375 | 4.106 | 6.224 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 102.228 | 5.982 | 0.189 | 4.327 |

| 02/21/25 | 109.6875 | 4.334 | 6.132 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 100.934 | 5.898 | 0.598 | 4.351 |

| 02/14/25 | 109.3125 | 4.398 | 6.196 | 0.9136 | T 4 ⅜ 01/31/32 | 99.868 | 5.927 | -0.273 | 4.371 |

| 02/07/25 | 109.2188 | 4.41 | 6.102 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 100.503 | 5.899 | 1.4 | 4.317 |

| 01/31/25 | 108.8125 | 4.479 | 6.163 | 0.9136 | T 4 ⅜ 01/31/32 | 99.411 | 5.94 | 0.845 | 4.309 |

| 01/24/25 | 108.40625 | 4.544 | 6.048 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 99.755 | 5.883 | 2.826 | 4.261 |

| 01/17/25 | 108.4844 | 4.531 | 6.054 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 99.827 | 5.893 | 3.025 | 4.255 |

| 01/10/25 | 107.3281 | 4.723 | 5.978 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 98.763 | 5.85 | 3.574 | 4.277 |

| 01/03/25 | 108.609375 | 4.51 | 6.062 | 0.9202 | T 4 ½ 12/31/31 | 99.942 | 5.932 | 1.345 | 4.386 |

| 12/27/24 | 108.375 | 4.595 | 6.593 | 0.7807 | T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 84.608 | 5.454 | -23.967 | 3.981 |

| 12/20/24 | 108.9219 | 4.512 | 6.63 | 0.7807 | T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 85.035 | 5.502 | -23.63 | 3.871 |

| 12/13/24 | 110 | 4.351 | 6.704 | 0.7807 | T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 85.877 | 5.563 | -29.064 | 4.148 |

| 12/06/24 | 111.609375 | 4.113 | 6.814 | 0.7807 | T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 87.133 | 5.673 | -28.27 | 3.968 |

| 11/29/24 | 111.3594 | 4.149 | 6.796 | 0.7807 | T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 86.938 | 5.676 | -31.025 | 4.092 |

| 11/22/24 | 109.953125 | 4.358 | 6.7 | 0.7807 | T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 85.84 | 5.592 | -35.393 | 4.356 |

| 11/15/24 | 109.8125 | 4.379 | 6.691 | 0.7807 | T 1 ⅞ 02/15/32 | 85.731 | 5.584 | -36.88 | 4.384 |

Dash for cash?

Ordinarily, these developments would be expected to buoy the value of the dollar, which is a “flight-to-safety” currency sought out by investors during times of crisis and acute uncertainty. Instead, the value of the dollar, too, plunged. In fact — relative to the predictions of a simple econometric model — the dollar fell by the greatest margin in the past four years.

Basis trade can be seen equivalently as an arbitrage between repos rates. When the U.S. government issued massive amounts of treasuries, the repo market was flooded in exchange for cash. The basis trade is a bet on the convergence of the repo rate and the implied repo rate. The implied repo rate is the rate at which you can borrow cash to buy a bond, and it is typically higher than the actual repo rate. The basis trade is a bet that the implied repo rate will converge to the actual repo rate, which would make the trade profitable. Even if global demand for dollars is soft, the immediate demand for dollars inside the repo system could surge.

Next steps

Basis traders act as warehousemen, providing liquidity to the Treasury market. But they are also highly leveraged, and the trade is inherently fragile, subject to margin and rollover risks.

A lesson not learned?

At the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, massive market volatility prompted lenders to make margin calls — a demand for more funds as collateral — on Treasury futures. At the same time, other nations’ central banks were dumping their Treasury holdings as part of their efforts to prop up their currencies. That caused cash bonds to underperform futures — the reverse of the conditions that the basis trade is meant to exploit — imposing significant losses on hedge funds.

It’s still unclear to what extent the basis trade contributed to the market turmoil in 2020, but there’s wide agreement that the rapid unwinding of positions amplified the volatility. In response, the Fed pledged to buy trillions of dollars’ worth of bonds to keep markets running smoothly and provided emergency funding to the market for short-term loans, known as repurchase agreements, or repos, that companies use to fund their operations. The Treasuries market eventually returned to normal.

“When stresses arise in the Treasury market, they can reverberate through the entire financial system and the economy,” he said.

A week later, the central bank got even more aggressive. In a surprise move before U.S. markets opened on Monday, March 23, the Fed removed earlier limits on the amounts of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities it would buy.

Since then, the scale of the Fed’s bond-buying already dwarfs purchases made in the wake of the last financial crisis. It bought nearly $1 trillion in Treasuries by April 1. Combined with its purchases of mortgage-backed securities, the Fed’s balance sheet now tops $5.8 trillion, up from less than $4.2 trillion in late February. The central bank has scaled back its buying to about $50 billion a day now.

The dramatic efforts are paying off. A key gauge of Treasury liquidity known as market depth, or the ability to trade without substantially moving prices, has normalized after plunging to levels last seen in the 2008 crisis, according to data compiled by JPMorgan.

The net holdings of cash Treasury bonds for primary dealers. (Kashyap et al., 2025)

The net holdings of cash Treasury bonds for primary dealers. (Kashyap et al., 2025) Given these risks, Gensler is worried about the size of the basis trade and the leverage used by hedge funds to execute it—and so is the International Bank for Settlements. The international institution that facilitates transactions between central banks warned in a September report that the “current build-up of leveraged short positions in U.S. Treasury futures is a financial vulnerability worth monitoring because of the margin spirals it could potentially trigger.” Griffin argues that the Treasury basis trade actually works to keep spreads low, enabling the Federal government to issue new debt at a lower cost. That’s because when hedge funds buy Treasuries to pair with their short positions in the basis trade, it puts downward pressure on spreads and yields. Griffin told the Robin Hood Investors Conference in October that the SEC is “consumed with this theory of systemic risk from this trade,” but the reality is taxpayers save “billions of dollars a year by allowing this trade to exist.” Citadel isn’t the only user of the Treasury basis trade; other major players in the market include Millennium Management, ExodusPoint Capital Management, Capula Investment Management, and Rokos Capital Management. And Griffin believes that if the SEC implements new rules that increase borrowing costs for these hedge funds’ favorite trade, it could cause a minor credit crunch.

After the 2020 debacle, basis trades largely subsided. But around early 2023, they began roaring back. The return of the trade has at least two causes: On the demand side, the Fed raised interest rates 11 times in just a year and a half, pushing up the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury to about 5%, the highest since 2007, and attracting large institutional investors to buy Treasuries in the futures market. Meanwhile, the Treasury Department has ramped up bond sales to fund swelling government deficits, putting downward pressure on the prices of bonds in the cash market. These forces have widened the gap between the futures and cash price of bonds, feeding interest in the basis trade.

Yields on 30-year Treasuries jumped in early April to briefly trade above 5%, a two-year high, even as Trump’s trade war hammered financial markets. Some market participants believe that the unwinding of basis trades contributed to the surprising yield surge, but there were limited signs of funding distress that would point to the disruption of the strategy. Other observers say factors such as the unwinding of another leveraged bond strategy — one that is designed to exploit the price differences between Treasuries and interest rate swaps, a financial instrument that allows investors to bet on borrowing costs — played a larger role in the bond sell-off. A broader retreat of foreign investors also contributed to the market volatility. (Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said on April 9 that there was nothing systemic about the “uncomfortable but normal deleveraging that’s going on in the bond market.”) The Treasury market stabilized somewhat by April 11, though the benchmark 10-year yield still posted its biggest weekly surge since 2001.

Back with a vengeance

(Bloomberg) – Tudor Investment Corp. trader Alexander Phillips lost about $140 million in April through earlier this week as President Donald Trump’s tariff barrage hammered financial markets, including US Treasuries. The mark-to-market losses on Phillips’ trading book erased his pre-April gains for 2025, and he was down by about $80 million for the year as of earlier this week, according to people familiar with the matter, asking not to be identified discussing private details.

The basis trade spreads have at times been positive (“in the money”) in recent months, making the trade profitable to initiate (before accounting for embedded options). The resurgence appears linked to macro conditions similar to 2018–2019: as interest rates moved up from the zero lower bound, demand for futures hedging by asset managers grew, widening the cash-futures basis. This created arbitrage opportunities that hedge funds have capitalized on. Indeed, asset managers have been increasing their long futures positions while hedge funds increase shorts, echoing the pattern of the earlier basis trade episode.

The revival of the basis trade in a structure involving sponsored repo clearing aligns with discussions in policy and academic circles about market structure reforms. Duffie (2020) famously argued that the U.S. Treasury market’s design needs an upgrade, particularly calling for broader central clearing of Treasury trades to reduce intermediaries’ balance sheet strain. Academic work by Hempel et al. (2023) also delves into why so much repo remains outside central clearing; one reason is not all trades benefit equally, but trades with net borrowing (like the basis trade) do particularly benefit from the netting and lower haircuts in sponsored repo. The current data — hedge funds hitting record sponsored repo borrowing — corroborate that central clearing usage has expanded for this trade. However, as the note and others point out, this doesn’t eliminate the risk, it just concentrates it differently (e.g., in the CCP and in those funds). Adrian et al. (2022) examine Treasury market liquidity and note that the intermediation capacity of dealers has not grown in line with the market, meaning non-dealer participants now bear more of the burden of market-making.

The basis trade is a clear example: it is essentially non-bank market-making between futures and cash. Adrian and colleagues highlight that while post-2008 regulations improved bank resilience, they may have reduced dealers’ willingness to absorb shocks, transferring risk to non-banks. The FEDS note’s findings underscore this: hedge funds are again highly leveraged, functioning as intermediaries, which is efficient in calm times but potentially destabilizing in crises. In sum, both the note and the literature suggest that market structure changes (like more central clearing and all-to-all trading) could help, but they also emphasize that simply shifting trades to clearinghouses doesn’t remove underlying leverage and liquidity risk (it might even enable larger positions due to easier financing).

What’s old is new again

LTCM specialized in bond arbitrage. Such trading entails taking advantage of anomalies in the price spread between two securities, which should have predictable price differences. They would bet divergences from the norm would eventually converge, as was all but guaranteed in time. LTCM was using 25x or more leverage when it failed in 1998. With that kind of leverage, a 4% loss on the trade would deplete the firm’s equity and force it to either raise equity or fail. The world-renowned hedge fund fell victim to the surprising 1998 Russian default. As a result of the unexpected default, there was a tremendous flight to quality into U.S. Treasury bonds, of which LTCM was effectively short. Bond divergences expanded as markets were illiquid, growing the losses on their convergence bets. The findings challenge the perception that external financing constraints are the primary driver of hedge fund fragility during crises. Instead, internal risk constraints and precautionary liquidity management play a critical role.

Hedge funds significantly reduced their UST exposures by approximately 20% on both the long and short sides during the crisis. Arbitrage positions declined by around 25%, indicating that hedge funds were net liquidity consumers rather than providers. Hedge funds increased cash holdings by approximately 26% and shifted to more liquid portfolios during the crisis, reflecting a “risk-off” approach to mitigate potential future losses. Kruttli et al. (2024) challenges the perception that external financing constraints are the primary driver of hedge fund fragility during crises. Instead, internal risk constraints and precautionary liquidity management play a critical role.

References

Barth, Daniel and R. Kahn (2023). “Hedge Funds and the Treasury Cash-Futures Disconnect.” OFR Working Paper 21-01. (Analysis of 2018–19 basis trade build-up).

Barth, Daniel, R. Jay Kahn, and Robert Mann (2023). “Recent Developments in Hedge Funds’ Treasury Futures and Repo Positions: is the Basis Trade ‘Back’?” FEDS Notes. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Aug 30, 2023.

Duffie, Darrell (2020). “Still the World’s Safe Haven? Redesigning the U.S. Treasury Market After the COVID-19 Crisis.” Hutchins Center Working Paper #62, June 2020.

Glicoes, Jonathan et al. (2024). “Quantifying Treasury Cash-Futures Basis Trades.” FEDS Notes, Mar 8, 2024. (Estimates size of basis trade using Form PF and TRACE data).

Hempel, Samuel et al. (2023). “Why is So Much Repo Not Centrally Cleared?” OFR Brief 23-01. (Discussion of cleared vs. uncleared repo use).

IMF Global Financial Stability Report (April 2024). “Financial Fragilities Along the Last Mile of Disinflation.” (Hedge fund basis trade risks and concentration).

Kashyap, Anil K., Jeremy C. Stein, Jonathan L. Wallen, and Joshua Younger (2025). “Treasury Market Dysfunction and the Role of the Central Bank.” BPEA Conference Draft, Spring.

Kruttli, Mathias et al. (2021). “Hedge Fund Treasury Trading and Funding Fragility: Evidence from the COVID-19 Crisis.” FEDS Working Paper 2021-038. (Documents hedge funds’ deleveraging in Mar 2020).

Kruttli, Mathias S., Phillip Monin, Lubomir Petrasek, and Sumudu W. Watugala (2024). “LTCM Redux? Hedge Fund Treasury Trading, Funding Fragility, and Risk Constraints.” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3817978 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3817978. (Examines hedge fund behavior during the March 2020 crisis).

Schrimpf, Andreas, Hyun Song Shin, and Vladyslav Sushko (2020). “Leverage and Margin Spirals in Fixed Income Markets during the Covid-19 Crisis.” BIS Bulletin No. 2.

Vissing-Jorgensen, Annette (2021). “The Treasury Market in Spring 2020 and the Response of the Federal Reserve.” Journal of Monetary Economics 124:19-47.